The village that time forgot

12th November 2025

Melton Constable turntable with 4MT engines, courtesy of Melton Constable History Society

Local author Caroline McGhie travels back to early 20th century North Norfolk to share the inspiration behind her debut novel The Sitter

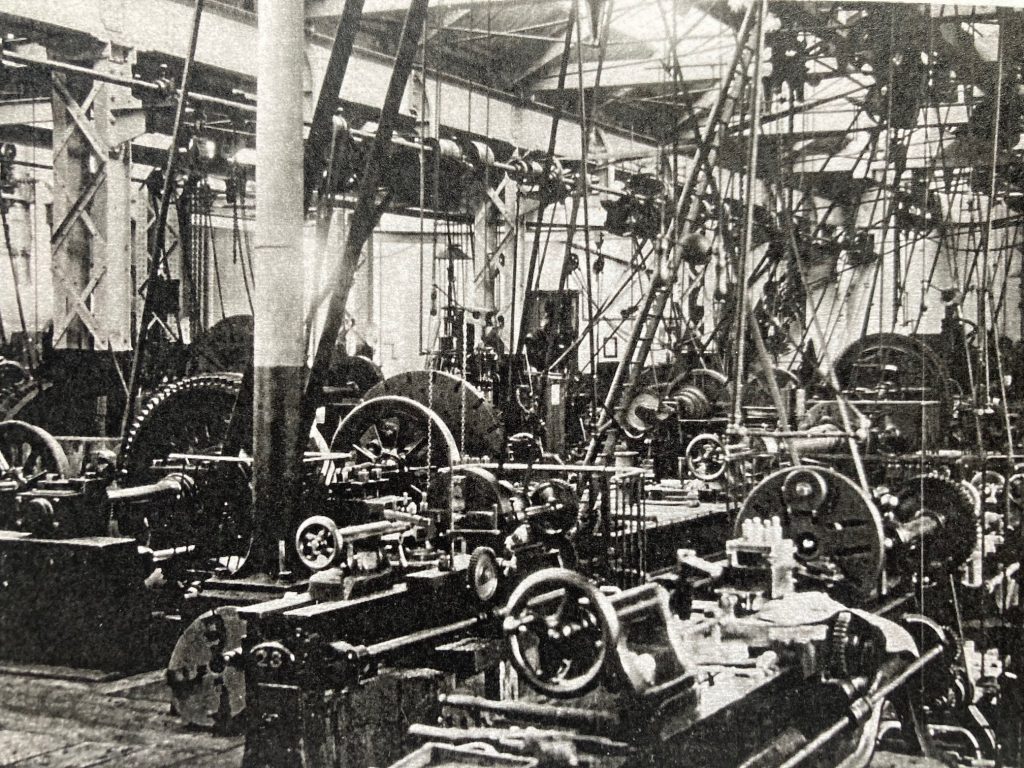

When I first drove through Melton Constable, I realised I was somewhere very unusual. The houses weren’t made of picturesque Norfolk flint, front doors facing away from the wind blowing off the North Sea. I was instead surrounded by tiny industrial brick terraces. Vast railway buildings lurked down back lanes, entirely derelict. It seemed to have been built in the middle of nowhere. An entire community, I would soon discover, had been created to serve an enormous railway hub called The Works. It was a forgotten railway village and I was completely drawn in by it.

I stopped the car and looked at the houses, overgrown allotments, boarded-up Victorian railway workshops and was astonished to find a brightly painted church made of corrugated iron that I later learned was known as The Tin Church of Burgh Parva. As I drove away, I realised the distant hedge boundary marked what had once been a railway line.

All writers need a stroke of luck and mine was to meet an old lady called Phyllis Youngman, who welcomed me into her house on the outer edge of Melton Constable. She was confined to her chair but had appointed herself the fierce keeper of village memory. The Works had shut down in the 1930s, and when the railway closures followed in the 50s and 60s she began to collect photographs, diaries, documents, and even kept old railway carriages plus an entire ticket office in her garden. Over tea and biscuits once a week she shared her collection with me and wanted the story of the village to be told. One evening she invited descendants of railway families round to share their memories too.

Melton Constable. I re-named it Swanton Stoke, scrolled back to 1900-1901, and invented a superintendent, a manager, upholsterers, trimmers, clerks, coal shovellers, engine drivers, a gang of boys, and got the trains running again. The Sitter is filled with the optimism of the new century and foreshadows the enormous social changes about to occur between the classes and sexes.

The story follows the life of young baker’s boy Jack Stamp who develops a crush on Rosie, a beautiful newcomer who steps off the train one evening, bringing with her a mysterious past. Through her eyes the reader sees the village as it was over a century ago: “Night after night she was woken by the noise from The Works and the comings and goings of the trains. The village lived by the trains. There was no need for clocks or timepieces. As the darkness of winter deepened, the gas lamps glowed longer and she became accustomed to the sound of men scraping and clanging, the blow of whistles, the hissing of steam, the roar of the engines.”

Jack in turn describes the hierarchy built into the very streets of a village governed by the coming and going of trains, the rhythm of bible readings and bread making. “On this side of the village we have to make do with lamps and water from the pump at the end of the road. We are called The Privates because the houses weren’t built by the Railway Company but by the landlords who rent them to us. Billy lives on the other side of the main road in a house built by the Railway Company, with water and gas laid on, so he doesn’t have to fetch water. The Railway Company takes their rent off the men’s wages.” Echoes of Melton Constable are palpable.

Through Jack’s eyes we get an impression of The Works when he sneaks in to steal a jemmy as a schoolboy dare. “The gas lamps light up the polished bodies of the carriages, and the workmen’s silhouettes cast huge shadows against the sheds. The place is peopled by so many giants it is difficult for me to sort human from shadow… A filthy stinking job. The lads are busy with wads of cotton waste. They guard them fiercely and hide them from each other as there aren’t enough to go round. Waste to them is like gold dust. A funny sort of gold dust is all I can say.”

Today Melton Constable’s works is bricked up and the railways have gone, but the houses remain and Phyllis Youngman, who has since died, would be pleased to know that the community is finally coming together to celebrate its railway heritage. The Friends of Briston and Burgh Parva Churches have won a £23,500 grant from Historic England as part of the Everyday Heritage Grant Project to celebrate working-class history. ‘We’ve started lots of groups,’ says Shannon Howell-Fuller, community engagement manager for the Friends. ‘A history group, a photography group, a group gathering railway memories from older residents, and an embroidery group producing a work by the artist John Jackson.’

A history website, funded by Historic England, is already up and running (www.melton-constable-history.co.uk) and stories from the past are coming in. Some residents have hung on to old railway lamps, stationmaster’s uniforms and railway signs which will be exhibited at a festival in May 2026 to bring together all the work they have been doing. Shannon says there will be talks, guided walks and a 360-degree animation of the station as it once was.

The Sitter contrasts what was going on in the world of art and science in London with the lives of hardworking railwaymen and fishermen in Norfolk and Rosie brings a whiff of scandal into what was a deeply religious community. She gives Jack a gift of a fly trapped in amber, a symbol for things past which still carry meaning for us today. Jack Stamp treasures it to the end. “Mother leaves rag rugs, Father leaves his book of recipes, the men leave clean carriages and trains that run on time, Flinty Daredevil leaves his boat, I leave my diaries,” he thinks. “We all make leavings for people to find one day in the future.” At last, in this year which marks the 200th anniversary of the first passenger train, Melton Constable is doing just that.

Snapshots of Cromer

The North Norfolk landscape with its huge skies, marshes and windmills is a wonderful backdrop for any writer, and Cromer at the start of the 20th century provides a rowdy social melting pot. Thanks to the railway, it had already transformed from a fishing town into a fashionable holiday destination. Extended families, complete with boys in sailor suits, nannies, pets and hula hoops, spilled off the trains to occupy the homes of fishermen who moved out for the duration of the summer. When Cromer Pier opened in 1901, the great and the good flocked to party and picnic.

In The Sitter we see the baker’s boy Jack Stamp visiting his Cromer cousins and running wild in high winds through streets, dodging round fishermen, crab dressers and boat builders. When a great storm blows up, he is awed to see the strength required for the fishermen to heave the lifeboat into the water, and by the stoicism of the women who sit up all night waiting for them to come home.

The Sitter by Caroline McGhie is available through all good bookshops or direct from Waterland Books, www.waterlandbooks.co.uk, price £12.99 plus postage and packing